It’s rare that I feel it appropriate to comment on my own personal experiences with Anderson shows when writing articles for this website, and yet on this anniversary of Gerry Anderson’s birth many fans understandably reflect on what his shows still mean to them. With that in mind, I find myself considering my own reasons for returning to them again and again.

To begin with, I find myself revisiting certain shows far more than others (with some of the very early shows and other oddities not really getting much of an airing at all) but that comes down largely to personal preference, and everyone's tastes are different. Certainly some Anderson shows enjoy a higher level of popularity and a greater public profile than others, but the fact that all of them have their fans says a lot about their quality and charm. My personal tastes cover most of the colour shows, along with

Supercar and

Fireball XL5, with particular favourites being both versions of

Captain Scarlet,

Joe 90,

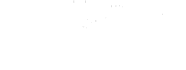

UFO,

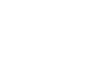

Space:1999, and

Terrahawks, with

Thunderbirds,

Stingray and

Space Precinct also in strong support.

The common themes running throughout all of these shows are imaginative ideas, great characters, strong scripts, occasionally an offbeat sense of humour and fun (sometimes tempered with a streak of darkness or pessimism), and the overall sense that these were television shows being produced as if they were feature films – with visual spectacle to match. Even when first being introduced to the worlds of Anderson via the 1991 BBC repeats of

Thunderbirds at age seven, it was clear that nothing else being shown on television at the time looked anything like it.

That ‘movies for television’ style sums up a great many of the Anderson shows, particularly during the 1960s. Granted in the case of the shows produced during the ITC era that quality certainly reflected the advantage of having a higher-than-average budget for a children’s series of the time, but it also reflects Gerry’s desire to be making the very best work possible in the hope of getting the feature film work he so craved. In attempting to reach those heights his shows also became synonymous with technological advancements; most notably the development of the puppetry process used on

Twizzle and

Torchy into the Supermarionation technique that brought

Thunderbirds,

Captain Scarlet and more to life, but also the numerous special effects techniques pioneered by

Stingray,

UFO and

Space:1999 (which would resonate throughout the film industry for decades), to the stop motion worlds of

Dick Spanner and

Lavender Castle, and the early CGI of

Space Precinct and

New Captain Scarlet. That pioneering spirit still resonates in the shows and with their viewers today, to the extent where even in the rare productions when things don’t work perfectly you’re almost inclined to give it a pass precisely because nobody else was attempting anything even remotely similar at that time.

When things are working perfectly, of course, there’s nothing to touch them for action and excitement, from the nail-biting conclusions of

Trapped in the Sky,

Terror in New York City and

The Mysterons to the apocalyptic finale of

Breakaway, the UFO vs Mobiles battle of

The Sound of Silence, or the pulse-pounding action scenes of

Time to Kill or

Rat Trap - with an awful lot of spectacular explosions and star vehicle launch sequences in between.

Spectacular special effects created merely in support of a thin story or weak characters would be a hollow thing, of course, and so it’s to the credit of all involved that the Anderson shows incorporated a host of memorable characters brought to life by talented performers (despite the tired, unfounded and lazy criticism often thrown in the direction of the live action shows). We cared about these characters, and wanted to see them triumph over adversity. Not only that, but the scripts themselves were for the most part pitched towards a family audience rather than a child one, with the result being shows that had something for everyone. In the case of very young viewers, the sense of being treated with the same respect and intelligence as adults may not have even registered with them – but it’s a rare thing in the entertainment industry, and one that has surprised many people upon revisiting the shows all these years later.

That’s one of the things that makes returning to these shows again and again so rewarding. It isn’t about revisiting our childhoods for an easy fix of nostalgia; if it were, they’d be entertaining for possibly an episode or two before the experience became pointless. The simple truth is that, incredibly, with many of them approaching sixty years of age (or more) they still hold up exceptionally well. They held up at the time. They held three decades later when my generation were discovering them through the 1990s BBC repeats. And they still hold up today, three more decades later, many of them looking better than they did when they were first aired thanks to High Definition Blu-ray. The fact that they continue to appeal to new viewers is proof enough of that. The attitude among those who created them to create the very best shows that they could ensures that these series will live forever.

It’s that attitude that I find most interesting when looking back at the Anderson universe, particularly during the ‘golden age’ of the 1960s. Despite the huge budgets and importance of international sales, the idea of the shows being frequently repeated for decades to come would have been dismissed as ludicrous by anyone involved in their production. There was no reason to suppose that anyone would ever be looking at them even five years after they were broadcast, much less fifty or more – so why go to so much trouble to make a production that in theory was going to have a very short shelf life look, feel and sound as good as possible?

The answer brings us back to the big screen, to the films that had inspired Anderson to become a filmmaker, and his drive to be producing Hollywood-style epics no matter what the subject matter of his current puppet television series. That aspiration seems to have inspired those who came into his orbit; the writers, actors, special effects crews, musicians, puppeteers, and more that worked on his shows.

“Let’s make this series as good as it can possibly be” is easily said, and yet it seems that that attitude, coupled with a huge amount of creative freedom on multiple fronts, gave those who worked with him the confidence to say

“yes; we will make this series as good as it can possibly be.”

That is where I feel the greatest strength of these shows can be found; in the perfect storms of circumstance and creativity where those talents were allowed to flourish again and again across the decades. From the very first moment the Twizzle puppet went before the cameras at Islet Park, to the day the last computer that created

New Captain Scarlet was switched off for the final time, Gerry Anderson was the man who assembled the very best talents and encouraged them to deliver some of the very best television shows the world has ever seen. Yet no one man can make a television series or a film, and there are certainly moments when the name of Gerry Anderson seems to eclipse the contributions of all others involved in his shows – although when discussing the run of shows from 1957’s

The Adventures of Twizzle to 2005’s

New Captain Scarlet as a single body of work,

‘the Gerry Anderson shows’ is certainly an easier phrase to say than a longer more convoluted one that accounts for absolutely everyone who worked on them across those five decades.

Yet as we celebrate Gerry Anderson’s birthday and the shows and films he produced, we absolutely should be looking to all those who worked with him as well; Sylvia Anderson, Reg Hill, Arthur Provis, John Read, Derek Meddings, Barry Gray, Brian Johnson, Shane Rimmer, David Graham, Ed Bishop, Alan Fennell, David Lane, Bob Bell, Christine Glanville, David Elliott and Mary Turner are but the smallest handful of examples of people who also produced the very best work possible in the service of

Thunderbirds and all the other shows. A mere sixteen names picked at random out of hundreds, illustrating again just how difficult it is to give everybody the recognition they deserve when summing the shows up in a single sentence – particularly when all their exceptional contributions were in the service of so extraordinary a final product.

But in the end, I feel what draws me back to the Anderson shows again and again – beyond the guarantee of quality entertainment that has yet to be paralleled on British television – is the chance to experience again the work of the many many talented artists and creatives who brought them all to life. The shows are fantastic, but only because the people who made them were. The idea of a group of skilled people realising adventures at the furthest reaches of space or the bottom of the sea on a weekly basis, or of a team of artists working together to create a spectacular children’s series that not only appealed to grown-ups but continues to hold the same appeal decades later, is a very very special and inspiring one – and arguably, something British television needs much more of.

Across more than five decades, Gerry Anderson was assembling such teams again and again to produce what he always hoped would be his biggest and best series yet. Although he himself may never have felt that any of them achieved the success he had been hoping for, the fact that all of them are still being watched and enjoyed all these years later is a testament not only to the strength of the ideas and concepts he devised, but also all those he took along on the journey of bringing them to our screens.

It’s rare that I feel it appropriate to comment on my own personal experiences with Anderson shows when writing articles for this website, and yet on this anniversary of Gerry Anderson’s birth many fans understandably reflect on what his shows still mean to them. With that in mind, I find myself considering my own reasons for returning to them again and again.

To begin with, I find myself revisiting certain shows far more than others (with some of the very early shows and other oddities not really getting much of an airing at all) but that comes down largely to personal preference, and everyone's tastes are different. Certainly some Anderson shows enjoy a higher level of popularity and a greater public profile than others, but the fact that all of them have their fans says a lot about their quality and charm. My personal tastes cover most of the colour shows, along with Supercar and Fireball XL5, with particular favourites being both versions of Captain Scarlet, Joe 90, UFO, Space:1999, and Terrahawks, with Thunderbirds, Stingray and Space Precinct also in strong support.

The common themes running throughout all of these shows are imaginative ideas, great characters, strong scripts, occasionally an offbeat sense of humour and fun (sometimes tempered with a streak of darkness or pessimism), and the overall sense that these were television shows being produced as if they were feature films – with visual spectacle to match. Even when first being introduced to the worlds of Anderson via the 1991 BBC repeats of Thunderbirds at age seven, it was clear that nothing else being shown on television at the time looked anything like it.

It’s rare that I feel it appropriate to comment on my own personal experiences with Anderson shows when writing articles for this website, and yet on this anniversary of Gerry Anderson’s birth many fans understandably reflect on what his shows still mean to them. With that in mind, I find myself considering my own reasons for returning to them again and again.

To begin with, I find myself revisiting certain shows far more than others (with some of the very early shows and other oddities not really getting much of an airing at all) but that comes down largely to personal preference, and everyone's tastes are different. Certainly some Anderson shows enjoy a higher level of popularity and a greater public profile than others, but the fact that all of them have their fans says a lot about their quality and charm. My personal tastes cover most of the colour shows, along with Supercar and Fireball XL5, with particular favourites being both versions of Captain Scarlet, Joe 90, UFO, Space:1999, and Terrahawks, with Thunderbirds, Stingray and Space Precinct also in strong support.

The common themes running throughout all of these shows are imaginative ideas, great characters, strong scripts, occasionally an offbeat sense of humour and fun (sometimes tempered with a streak of darkness or pessimism), and the overall sense that these were television shows being produced as if they were feature films – with visual spectacle to match. Even when first being introduced to the worlds of Anderson via the 1991 BBC repeats of Thunderbirds at age seven, it was clear that nothing else being shown on television at the time looked anything like it.

That ‘movies for television’ style sums up a great many of the Anderson shows, particularly during the 1960s. Granted in the case of the shows produced during the ITC era that quality certainly reflected the advantage of having a higher-than-average budget for a children’s series of the time, but it also reflects Gerry’s desire to be making the very best work possible in the hope of getting the feature film work he so craved. In attempting to reach those heights his shows also became synonymous with technological advancements; most notably the development of the puppetry process used on Twizzle and Torchy into the Supermarionation technique that brought Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and more to life, but also the numerous special effects techniques pioneered by Stingray, UFO and Space:1999 (which would resonate throughout the film industry for decades), to the stop motion worlds of Dick Spanner and Lavender Castle, and the early CGI of Space Precinct and New Captain Scarlet. That pioneering spirit still resonates in the shows and with their viewers today, to the extent where even in the rare productions when things don’t work perfectly you’re almost inclined to give it a pass precisely because nobody else was attempting anything even remotely similar at that time.

When things are working perfectly, of course, there’s nothing to touch them for action and excitement, from the nail-biting conclusions of Trapped in the Sky, Terror in New York City and The Mysterons to the apocalyptic finale of Breakaway, the UFO vs Mobiles battle of The Sound of Silence, or the pulse-pounding action scenes of Time to Kill or Rat Trap - with an awful lot of spectacular explosions and star vehicle launch sequences in between.

That ‘movies for television’ style sums up a great many of the Anderson shows, particularly during the 1960s. Granted in the case of the shows produced during the ITC era that quality certainly reflected the advantage of having a higher-than-average budget for a children’s series of the time, but it also reflects Gerry’s desire to be making the very best work possible in the hope of getting the feature film work he so craved. In attempting to reach those heights his shows also became synonymous with technological advancements; most notably the development of the puppetry process used on Twizzle and Torchy into the Supermarionation technique that brought Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and more to life, but also the numerous special effects techniques pioneered by Stingray, UFO and Space:1999 (which would resonate throughout the film industry for decades), to the stop motion worlds of Dick Spanner and Lavender Castle, and the early CGI of Space Precinct and New Captain Scarlet. That pioneering spirit still resonates in the shows and with their viewers today, to the extent where even in the rare productions when things don’t work perfectly you’re almost inclined to give it a pass precisely because nobody else was attempting anything even remotely similar at that time.

When things are working perfectly, of course, there’s nothing to touch them for action and excitement, from the nail-biting conclusions of Trapped in the Sky, Terror in New York City and The Mysterons to the apocalyptic finale of Breakaway, the UFO vs Mobiles battle of The Sound of Silence, or the pulse-pounding action scenes of Time to Kill or Rat Trap - with an awful lot of spectacular explosions and star vehicle launch sequences in between.

Spectacular special effects created merely in support of a thin story or weak characters would be a hollow thing, of course, and so it’s to the credit of all involved that the Anderson shows incorporated a host of memorable characters brought to life by talented performers (despite the tired, unfounded and lazy criticism often thrown in the direction of the live action shows). We cared about these characters, and wanted to see them triumph over adversity. Not only that, but the scripts themselves were for the most part pitched towards a family audience rather than a child one, with the result being shows that had something for everyone. In the case of very young viewers, the sense of being treated with the same respect and intelligence as adults may not have even registered with them – but it’s a rare thing in the entertainment industry, and one that has surprised many people upon revisiting the shows all these years later.

That’s one of the things that makes returning to these shows again and again so rewarding. It isn’t about revisiting our childhoods for an easy fix of nostalgia; if it were, they’d be entertaining for possibly an episode or two before the experience became pointless. The simple truth is that, incredibly, with many of them approaching sixty years of age (or more) they still hold up exceptionally well. They held up at the time. They held three decades later when my generation were discovering them through the 1990s BBC repeats. And they still hold up today, three more decades later, many of them looking better than they did when they were first aired thanks to High Definition Blu-ray. The fact that they continue to appeal to new viewers is proof enough of that. The attitude among those who created them to create the very best shows that they could ensures that these series will live forever.

Spectacular special effects created merely in support of a thin story or weak characters would be a hollow thing, of course, and so it’s to the credit of all involved that the Anderson shows incorporated a host of memorable characters brought to life by talented performers (despite the tired, unfounded and lazy criticism often thrown in the direction of the live action shows). We cared about these characters, and wanted to see them triumph over adversity. Not only that, but the scripts themselves were for the most part pitched towards a family audience rather than a child one, with the result being shows that had something for everyone. In the case of very young viewers, the sense of being treated with the same respect and intelligence as adults may not have even registered with them – but it’s a rare thing in the entertainment industry, and one that has surprised many people upon revisiting the shows all these years later.

That’s one of the things that makes returning to these shows again and again so rewarding. It isn’t about revisiting our childhoods for an easy fix of nostalgia; if it were, they’d be entertaining for possibly an episode or two before the experience became pointless. The simple truth is that, incredibly, with many of them approaching sixty years of age (or more) they still hold up exceptionally well. They held up at the time. They held three decades later when my generation were discovering them through the 1990s BBC repeats. And they still hold up today, three more decades later, many of them looking better than they did when they were first aired thanks to High Definition Blu-ray. The fact that they continue to appeal to new viewers is proof enough of that. The attitude among those who created them to create the very best shows that they could ensures that these series will live forever.

It’s that attitude that I find most interesting when looking back at the Anderson universe, particularly during the ‘golden age’ of the 1960s. Despite the huge budgets and importance of international sales, the idea of the shows being frequently repeated for decades to come would have been dismissed as ludicrous by anyone involved in their production. There was no reason to suppose that anyone would ever be looking at them even five years after they were broadcast, much less fifty or more – so why go to so much trouble to make a production that in theory was going to have a very short shelf life look, feel and sound as good as possible?

The answer brings us back to the big screen, to the films that had inspired Anderson to become a filmmaker, and his drive to be producing Hollywood-style epics no matter what the subject matter of his current puppet television series. That aspiration seems to have inspired those who came into his orbit; the writers, actors, special effects crews, musicians, puppeteers, and more that worked on his shows. “Let’s make this series as good as it can possibly be” is easily said, and yet it seems that that attitude, coupled with a huge amount of creative freedom on multiple fronts, gave those who worked with him the confidence to say “yes; we will make this series as good as it can possibly be.”

That is where I feel the greatest strength of these shows can be found; in the perfect storms of circumstance and creativity where those talents were allowed to flourish again and again across the decades. From the very first moment the Twizzle puppet went before the cameras at Islet Park, to the day the last computer that created New Captain Scarlet was switched off for the final time, Gerry Anderson was the man who assembled the very best talents and encouraged them to deliver some of the very best television shows the world has ever seen. Yet no one man can make a television series or a film, and there are certainly moments when the name of Gerry Anderson seems to eclipse the contributions of all others involved in his shows – although when discussing the run of shows from 1957’s The Adventures of Twizzle to 2005’s New Captain Scarlet as a single body of work, ‘the Gerry Anderson shows’ is certainly an easier phrase to say than a longer more convoluted one that accounts for absolutely everyone who worked on them across those five decades.

It’s that attitude that I find most interesting when looking back at the Anderson universe, particularly during the ‘golden age’ of the 1960s. Despite the huge budgets and importance of international sales, the idea of the shows being frequently repeated for decades to come would have been dismissed as ludicrous by anyone involved in their production. There was no reason to suppose that anyone would ever be looking at them even five years after they were broadcast, much less fifty or more – so why go to so much trouble to make a production that in theory was going to have a very short shelf life look, feel and sound as good as possible?

The answer brings us back to the big screen, to the films that had inspired Anderson to become a filmmaker, and his drive to be producing Hollywood-style epics no matter what the subject matter of his current puppet television series. That aspiration seems to have inspired those who came into his orbit; the writers, actors, special effects crews, musicians, puppeteers, and more that worked on his shows. “Let’s make this series as good as it can possibly be” is easily said, and yet it seems that that attitude, coupled with a huge amount of creative freedom on multiple fronts, gave those who worked with him the confidence to say “yes; we will make this series as good as it can possibly be.”

That is where I feel the greatest strength of these shows can be found; in the perfect storms of circumstance and creativity where those talents were allowed to flourish again and again across the decades. From the very first moment the Twizzle puppet went before the cameras at Islet Park, to the day the last computer that created New Captain Scarlet was switched off for the final time, Gerry Anderson was the man who assembled the very best talents and encouraged them to deliver some of the very best television shows the world has ever seen. Yet no one man can make a television series or a film, and there are certainly moments when the name of Gerry Anderson seems to eclipse the contributions of all others involved in his shows – although when discussing the run of shows from 1957’s The Adventures of Twizzle to 2005’s New Captain Scarlet as a single body of work, ‘the Gerry Anderson shows’ is certainly an easier phrase to say than a longer more convoluted one that accounts for absolutely everyone who worked on them across those five decades.

Yet as we celebrate Gerry Anderson’s birthday and the shows and films he produced, we absolutely should be looking to all those who worked with him as well; Sylvia Anderson, Reg Hill, Arthur Provis, John Read, Derek Meddings, Barry Gray, Brian Johnson, Shane Rimmer, David Graham, Ed Bishop, Alan Fennell, David Lane, Bob Bell, Christine Glanville, David Elliott and Mary Turner are but the smallest handful of examples of people who also produced the very best work possible in the service of Thunderbirds and all the other shows. A mere sixteen names picked at random out of hundreds, illustrating again just how difficult it is to give everybody the recognition they deserve when summing the shows up in a single sentence – particularly when all their exceptional contributions were in the service of so extraordinary a final product.

Yet as we celebrate Gerry Anderson’s birthday and the shows and films he produced, we absolutely should be looking to all those who worked with him as well; Sylvia Anderson, Reg Hill, Arthur Provis, John Read, Derek Meddings, Barry Gray, Brian Johnson, Shane Rimmer, David Graham, Ed Bishop, Alan Fennell, David Lane, Bob Bell, Christine Glanville, David Elliott and Mary Turner are but the smallest handful of examples of people who also produced the very best work possible in the service of Thunderbirds and all the other shows. A mere sixteen names picked at random out of hundreds, illustrating again just how difficult it is to give everybody the recognition they deserve when summing the shows up in a single sentence – particularly when all their exceptional contributions were in the service of so extraordinary a final product.

But in the end, I feel what draws me back to the Anderson shows again and again – beyond the guarantee of quality entertainment that has yet to be paralleled on British television – is the chance to experience again the work of the many many talented artists and creatives who brought them all to life. The shows are fantastic, but only because the people who made them were. The idea of a group of skilled people realising adventures at the furthest reaches of space or the bottom of the sea on a weekly basis, or of a team of artists working together to create a spectacular children’s series that not only appealed to grown-ups but continues to hold the same appeal decades later, is a very very special and inspiring one – and arguably, something British television needs much more of.

Across more than five decades, Gerry Anderson was assembling such teams again and again to produce what he always hoped would be his biggest and best series yet. Although he himself may never have felt that any of them achieved the success he had been hoping for, the fact that all of them are still being watched and enjoyed all these years later is a testament not only to the strength of the ideas and concepts he devised, but also all those he took along on the journey of bringing them to our screens.

But in the end, I feel what draws me back to the Anderson shows again and again – beyond the guarantee of quality entertainment that has yet to be paralleled on British television – is the chance to experience again the work of the many many talented artists and creatives who brought them all to life. The shows are fantastic, but only because the people who made them were. The idea of a group of skilled people realising adventures at the furthest reaches of space or the bottom of the sea on a weekly basis, or of a team of artists working together to create a spectacular children’s series that not only appealed to grown-ups but continues to hold the same appeal decades later, is a very very special and inspiring one – and arguably, something British television needs much more of.

Across more than five decades, Gerry Anderson was assembling such teams again and again to produce what he always hoped would be his biggest and best series yet. Although he himself may never have felt that any of them achieved the success he had been hoping for, the fact that all of them are still being watched and enjoyed all these years later is a testament not only to the strength of the ideas and concepts he devised, but also all those he took along on the journey of bringing them to our screens.

![Thunderbirds Comic Anthology Volume One [HARDCOVER] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/thunderbirds-comic-anthology-volume-one-hardcover-8030771.jpg?v=1751089031&width=720)

![All Sections Alpha: The Making of Space: 1999 [HARDCOVER] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/all-sections-alpha-the-making-of-space-1999-hardcover-7498116.png?v=1757766647&width=720)

![Stingray Comic Anthology Volume Two – Battle Lines [HARDCOVER] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/stingray-comic-anthology-volume-two-battle-lines-hardcover-107681.jpg?v=1738856151&width=720)

![Stingray W.A.S.P. Technical Operations Manual Standard Edition [HARDCOVER] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/stingray-wasp-technical-operations-manual-standard-edition-hardcover-112278.jpg?v=1749664163&width=720)

![Stingray WASP Technical Operations Manual Special Limited Edition [HARDCOVER BOOK] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/stingray-wasp-technical-operations-manual-special-limited-edition-hardcover-book-991914.jpg?v=1749657538&width=720)

![Stingray: The Titanican Stratagem – Signed Limited Edition [HARDCOVER NOVEL] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/stingray-the-titanican-stratagem-signed-limited-edition-hardcover-novel-129251.jpg?v=1740558711&width=720)