Pilots in Parallel: UFO v Space: 1999

Share

Share

Gerry Anderson programmes often feature similar premises, vehicles, characters and wider thematic ideas at work. Quite often, it falls to each series' pilot episode to introduce each of these key elements to the audience. But just how similar are these ideas? Does one series execute these shared themes better than the other?

We're pitting two similar Anderson pilots against each other to determine which one stands as the best viewing experience!

SHADO is Go

UFO and Space: 1999 are often considered to be Gerry and Sylvia's greatest creative achievements as television producers. Building on a decade's work of puppetry and a modest handful of live-action productions, UFO's brief, single-series existence nonetheless feels like a cathartic victory lap for the Andersons, whilst Space: 1999 would prove to be one of the most ambitious sci-fi series produced for television. Having created several children's puppet series which increasingly pushed expectations of how mature and sophisticated children's television could be, Century 21 Productions' final venture would abandon marionettes entirely and marry the spectacular model work with a fully live-action cast.

Identified, the pilot episode for UFO (and, quite appropriately, the first of the series' episodes to be produced), expertly lays the groundwork for the downbeat moods that Century 21 Productions' solitary live action TV series would exploit upon. UFO was always one of the Andersons' more deceptive series. On the surface, it carries many recognisable hallmarks of an Anderson series - secret organisation protecting the world, fantastically futuristic vehicles, memorable alien enemies. But UFO was much less straight-forward than just being a bog standard alien invasion affair. UFO places much of its emphasis on the very real emotional tolls endured by those who defend us. The intense security of SHADO means that no SHADO personnel can ever reveal to the world what their roles are in keeping that world safe. So often throughout the series, we see the depressing fallout of how SHADO, and humanity in general, reacts to an invasion of organ-harvesting aliens.

UFO is easily dominated by Ed Bishop's arresting performance as SHADO commander Ed Straker, a man who cannot risk letting his world-weariness of undertaking such an impossible role be witnessed by too many people. Identified matches the aesthetics of earlier Anderson pilots Trapped in the Sky and The Mysterons by introducing us to SHADO's covert set-up and its fantastic fleet of machines, but it's the human cost of this invisible war between man and alien which Identified truly gets right the first time. As SHADO grapples with its first Earth-based encounter with a UFO, it falls to Straker to remind Lieutenant Keith Ford that SHADO can never risk revealing itself to the world it protects. To keep the UFO threat under a blanket of secrecy, families are left in deliberate limbo over loved ones attacked by aliens. In UFO, trauma extends beyond death, something which Identified highlights with bold confidence.

Elsewhere, Identified doesn't skip on its other winning elements, namely the gruesome body horror involved when SHADO recovers and examines its first alien invader, along with the thrilling special effects used in SHADO's hardware. The episode colours in SHADO's global reach by showcasing its impressively eclectic defences. SHADO Interceptors, Skydiver and Sky-1 are the mecha stars of Identified, all springing into action against the invading UFOs to enhance the series' sci-fi action credentials to exciting effect. Not since Thunderbirds had we seen an Anderson series display a covert organisation with such a far-reaching hold over the world it protects. No area of the Earth is left undefended, whilst the additional appearance of SHADO Moonbase adds to the sense of galactic scale which UFO often married with its more withdrawn, human-interest attitudes.

Into the Void

By the time Space: 1999 began in September 1975, Century 21 Productions had now disbanded, but Gerry, Sylvia and producer Reg Hill regrouped as Group Three Productions. Space: 1999 emerged out of the ruins of UFO's stalled second series, with regular financial backer Lew Grade insisting that American-based actors, writers and directors be brought in to help trans-Atlantic sales. Breaking tradition then with how Anderson pilot episodes had been written up until then, George Bellek was hired to write the series' pilot episode, initially titled The Void Ahead, along with fellow American Lee H. Katzin in the director's chair. This would be a fresh attempt at the beginning of Space: 1999 after the Andersons' own self-written venture, Zero-G, went unutilised. After nearly a decade of establishing the format for each of their productions by writing the pilot episodes themselves, the unused Zero-G marks the end of Gerry and Sylvia's scriptwriting collaborations. Indeed, the making of Breakaway would become a far cry from Identified, which was written by Gerry and Sylvia with regular scriptwriter Tony Barwick, and with Gerry directing. Now, much of the creative reins were in other hands.

The Void Ahead itself would be rechristened into Breakaway, with extensive rewrites by Christopher Penfold, and despite Bellek's disconnect from the Andersons' past efforts, there's an undeniable thematic link of morosity between Identified and Breakaway. Space: 1999's own pilot trades in the intimate, closed-off nature of SHADO for the universally sprawling scope of Space: 1999, with Breakaway showcasing how Moonbase Alpha's continuing pileup of atomic waste from Earth culminates into a gargantuan explosion that propels the moon out of the Earth's orbit. Space: 1999 catapults the 311 men and women of Moonbase Alpha into a cosmically philosophical journey across the stars as the Alphans' regular adventures with surreal cosmic phenomena brings with them questions of humanity's place in an incomprehensibly vast universe.

Undoubtedly one of the most morosely intense episodes of television produced by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, Breakaway is another fine example of how an Anderson pilot typically weaves together its core characters, technology, themes and morality into an riveting introductory adventure. An appropriately apocalyptic atmosphere is drenched across this episode from beginning to end, establishing the overall tone that the series (well, the *first* season, at least!) would continue and gearshift into varying directions across those first 24 episodes. An inescapable sense of something horrible brewing helps make Breakaway such an engrossing affair to watch unfold, as the mystery of several Alphan astronauts falling ill to an unseen virus coalesces into the eventual explosion of the moon's nuclear waste.

Where many future episodes would thrust Moonbase Alpha into bizarre cosmic grandeur, Breakaway is set against a backdrop of bureaucratic power play between the Earth and the moon. Arriving on Moonbase Alpha as its new leader when taking over from Commander Gortski, Commander Koenig gradually learns that the strange illnesses experienced by Alphan pilots is far more severe than he was led to believe by the Earth-based Commissioner Simmonds. Breakaway paints a bleakly unsympathetic picture of how far the powers that be are willing to exploit human life in the pursuit of planetary conquest.

The simmering tension between all the various key players in Breakaway reaches boiling point when the moon is eventually blasted out of the Earth's orbit, just as the truth behind the astronauts' mystery illness and eruption of the moon's nuclear waste are both connected. But even with the Alphans' lives turned upside down as the moon is torn away from the Earth, plunging into the depths of space, Breakaway manages to end on a note of cautious optimism. The Alphans take note of the radio signals emanating from the known planet of Meta, which may just be able to support human life. Whilst the Meta subplot would be left unresolved, it feels like a deliberate choice to have such an apocalyptic episode end on a positive note. But this, of course, was just the beginning of Space: 1999…

Identifying the Winner

When Identified is so closely defined by its covert intimacy and Breakaway by its cosmic scope, is it perhaps unfair to pit these two against each other? Whilst both Identified and Breakaway are hugely conceptual in nature and remain enjoyably engaging watches, Breakaway definitely feel the more accomplished of the two. It’s perhaps not unfair to determine that Space: 1999 also carries the stronger cast. Where UFO is dominated by Straker, Space: 1999 carries the refreshing benefit of feeling more like an ensemble performance, naturally led by Martin Landau’s stoic, quietly arresting delivery of Commander Koenig. By comparison, UFO comes to feel admittedly restrained not just by the fact that Straker is so central to the series’ downbeat appeal, but that Bishop is clearly given more ample emotional material to work with compared to the others in the cast.

To UFO’s credit, it rarely feels like it’s struggling to shed its puppet predecessors. Rather, it feels like the work of professionals who feel freed and vindicated from the creative constraints of their marionette past. But Breakaway ultimately comes off as the more cinematically convincing viewing experience. If the puppet shows served as a springboard for UFO, then there’s the argument that UFO serves as that same springboard for Space: 1999. With its cosmically ambitious premise and enlivened creative DNA in its writing, directing and acting, Breakaway just about trounces Identified as the superior endeavour. However, both episodes still undeniably deliver on their premises to compelling effect, offering a pair of adventurously mature episodes of classic sci-fi television.

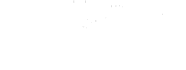

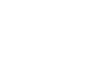

Discover more about the worlds of UFO and Space: 1999 with our popular range of Technical Operations Manuals and comic anthologies! To be the first to hear about the latest news, exclusive releases and show announcements, sign up to the Anderson Entertainment newsletter!

![Fireball XL5 World Space Patrol Technical Operations Manual [HARDCOVER BOOK] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/fireball-xl5-world-space-patrol-technical-operations-manual-hardcover-book-290050.jpg?v=1711729272&width=720)

![Stingray Comic Anthology Volume Two – Battle Lines [HARDCOVER] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/stingray-comic-anthology-volume-two-battle-lines-hardcover-107681.jpg?v=1738856151&width=720)

![Space: 1999 and UFO Book Bundle - Signed Limited Editions [HARDCOVER NOVELS] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/space-1999-and-ufo-book-bundle-signed-limited-editions-hardcover-novels-589446.jpg?v=1718836845&width=720)

![Stingray WASP Technical Operations Manual Special Limited Edition [HARDCOVER BOOK] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/stingray-wasp-technical-operations-manual-special-limited-edition-hardcover-book-991914.jpg?v=1732922875&width=720)

![Stingray: The Titanican Stratagem – Signed Limited Edition [HARDCOVER NOVEL] - The Gerry Anderson Store](http://gerryanderson.com/cdn/shop/files/stingray-the-titanican-stratagem-signed-limited-edition-hardcover-novel-129251.jpg?v=1740558711&width=720)